By Sandie Jessamine

This post includes descriptions of child abuse, sexual violence, carceral violence, addiction, overdose and suicide.

***

A grey-haired woman picked up her quill

and letting it guide her

she travelled inside her bones

the journey fuelled by a verdict of madness

that happened one borderline day

Norton Street in Leichhardt is Sydney’s little Italy. Garlic, mozzarella, a cinema and red wine. But not for me today. No smell. No sight. No sound. I drift along the street like the walking dead, filled with nothing more than choking dread.

It’s the autumn of 2015 and as I head past shopfronts and restaurants, I squint through sunglasses at a cobalt sky and involuntarily yell, ‘Liar. The world is not bright. Summer’s shadow has waned.’

Having failed to keep my madness behind closed lips, I continue on my way.

I stroll past an old man wearing a Fedora hat and a 1930s waistcoat. ‘Are those we never meet just phantoms passing by?’ a voice inside my head asks. An urge to touch him comes, to check if he is solid. No. My hair is too knotted, my clothes too dishevelled to pretend I’ll help him cross the road.

I stop at a café called Bar Italia. Toddlers lick gelatos, strawberry and chocolate forming tattoos on their chins. I buy a takeaway cappuccino. Taste. I must not run away or vanish totally from myself.

Not far to my destination now, a Federation house with a sign out the front, listing therapists. But no counselling session awaits, my therapist Alex peeling layers off my soul, trying to help me heal. Instead, Alex has received a report from a psychiatrist, one my employer sent me to, following my last mental breakdown. The report contains a mental health work fitness assessment I must read.

Alex stands in the doorway. The cotton shirts and soft trousers he loves, rarely change with the seasons. Comfortable. Predictable. He is so absorbed with trauma, writing papers and giving lectures when he isn’t seeing clients. Of his personal life I know only that he has a dog and grown children.

His face is grim. I suspect the worse as I sit in a scratchy armchair. Sun filters through the curtains, breaking the dimness. I’m never sure if it is the light of the room or talking about the past, but time often fades when I’m here.

For over a decade, Alex has helped me to manage Complex Post-traumatic Stress Disorder symptoms. In truth I had Complex-PTSD long before I met him, but he was the first to give my terrors a name.

Complex-PTSD is caused by prolonged and repetitive trauma from which there seems no escape. Child sexual and physical abuse. Imprisonment. Bullying. Domestic violence. Or being made to feel different, as if we don’t belong. At some phase in the lives of those who live with Complex-PTSD, we existed inside a nightmare from which there was no awakening. We might have physically left it behind, but we’re not convinced. And so parts of us re-enact trauma, compulsively, unconsciously, still searching for a way out.

Sometimes I don’t know who I am or where. Past and present merge. I might act and speak like a child and yet I am middle-aged. I watch this unfold from the corners of my mind where I’ve have been sequestered. But it’s doubtful I’ll remember my absence once the body is mine again. Just holes where time and I used to be.

Alex holds a tiny bottle of peppermint oil under my nose. The pungent scent startles me. I force myself to look around at the abstract paintings and a bookcase overflowing with therapy manuals. My therapist appears hazy, as if he exists behind smeared glass.

‘Sandie, you need a clear head to read this. It’s important you’re in your body.’

Behind him the printer whirs as the psychiatric report spits out.

***

My mental breakdown occurred in 2014, inside a New South Wales men’s prison where I taught creative writing to child sex offenders and corrupt police officers sentenced for their crimes. My father, now dead, had been in the final stage of cancer. My daughter – still alive, barely – had descended into drug addiction. I’d been in conflict with my boss. In a combustion of grief, fear, anger and longing, I collapsed internally. Traumatised child and teenage parts of my personality took over. Sami the teenage witch who was rather posh and loved poetry. Arhwah a needy little girl. And a dancing delinquent called Sandie, like me, a ‘me’ from a distant time.

Whilst in these altered states, I began hugging the inmates, dancing with them in the prison library, pleading with these prisoners to ‘Save me’.

‘From whom?’ the caged men asked.

‘From my ghosts.’

I taught in an isolated education building. There were no managers or custodial officers; some days there were no other teachers. One inmate who recognised my madness, began to experience his own when memories that haunted him were triggered. He cornered me with tales dark and twisted whenever we were alone. Murders. Muggings. Bodies mangled. He had once been a cop.

A prison chaplain discovered me sitting in an old cell with this inmate, holding his hands and singing ‘Kumbaya’. The chaplain joined us in song, although appearing sceptical that either of us had found God.

Other staff also remarked that I seemed disturbed, although no one thought it odd that the creative writing assignments I handed back to students had been signed by Sami the witch.

Months passed and rumours spread. But it was me who confessed to my bosses that it hadn’t always been me who’d inhabited my body at work.

***

The psychiatric report is eight pages long, heavy enough to crush me. I read through facts, half-truths, omissions and distortions. Is this the psych’s interpretation or did this mangled mess stem from me?

‘Ms Jessamine stated that inmate XX had not described sexual offences with a 7-year-old. Rather, he was describing child pornography about a 7-year-old. Inmate XX told Ms Jessamine that he thought she had regressed to the age of a 7-year-old girl. Ms Jessamine said she felt ‘scared and controlled and manipulated’.

Well, who in their right mind would expect that the sexually abused child they’d been decades ago, would awaken, hijack the body, and then discover they were locked in a prison with paedophiles?

I fling the report down, pull water from my bag, swig, splash some on my face, then continue reading.

Complex-PTSD symptoms are listed. Depression and self-loathing, a poor core notion of self, memories or flashbacks of past trauma, fear of abandonment, thoughts of deliberate self-harm, and episodic regression to childlike states or dissociation.

‘Some people…during dissociative experiences feel like they have adopted other personas. If this becomes a pattern, it is labelled Dissociative Identity Disorder. It could be argued that this would be an appropriate diagnosis for Ms Jessamine.’

‘Years can pass without me switching between personality states. How can I have Dissociative Identity Disorder?’ I ask Alex. The disorder was once called Multiple Personality Disorder.

‘You’re what’s termed Apparently Normal, dissociated from the trauma and parts of you that hold it. How many times have you complained you felt like a cardboard figure? Dissociation by nature is hidden when you’re in a rational mind.’

I snort. Ludicrous. Yet I vaguely recall having talked to Alex about this before.

‘Keep reading, Sandie. That’s not his diagnosis.’

‘Borderline Personality Disorder (or Complex-PTSD), with episodic dissociation and regression.’

‘Borderline Personality Disorder? He’s turned my PTSD into a personality disorder and one of the most stigmatised. Tell someone you’re a prison teacher who has PTSD and they say “Yeah, yeah but this borderline stuff…” People will think I’m going to yell at them or kill myself. The medical profession. Society. They do this to women. Make out we’re the problem, instead of the shit that happens to us.’

Alex swivels in his chair while mumbling about addressing this later. To go there now would lead down a rabbit hole, not to the end of this document.

‘Do you agree with this?’ I rant. ‘I know people who have BPD. They self-harm. Explode with rage. Eat and vomit. Vomit. Eat. And don’t get me started on Suicidal. That hasn’t been me for decades.’

‘Squish anyone into a list of symptoms and you’ll find an arm missing, a leg outside the box,’ he says.

‘I’ve been lumbered with a label that’s a bikini on my fat middle-aged body.’

I reach the final verdict.

‘In my opinion as a psychiatrist, Ms Jessamine is not fit for work as a teacher within the Correctional System.’

The inevitable. I stand on a footbridge in a thundering storm. Will I ever be secure again? I’ve taught in prisons for fourteen years. The unemployment scrapheap beckons and now I’m well into my fifties, how will I land another job, especially after this?

I put my face in my hands and wail until my sobs release me. Only then do I straighten my spine.

There’s a Greek word, Kairos. It means an opening in time that creates an opportunity, a spiritual moment when the divine takes over. I know what I need to do.

‘Alex, I’m going to unravel this personality disorder. I’m going to write my story, my way.’ I nod with emphasis.

‘I’m turning myself into a storyteller, a wise old borderline crone. I love that word. Crone.’ I rhyme it with a groan. Borderline and Crone. Two words with the connotation, crazy woman.

‘Alex, decades ago, I had an identical breakdown inside a juvenile prison I was locked up in. I suspect I’ll find my answers there. I’m going to set my younger self and her stories free.’

‘Good. You’re burned out anyway. About time you got out of gaol,’ he says, misunderstanding me.

I look him in the eye. ‘Not yet. I will need to find a way to get back into one. Kamballa Special Unit at Parramatta, a place that once held the wildest and most mentally unstable girls in custody.’

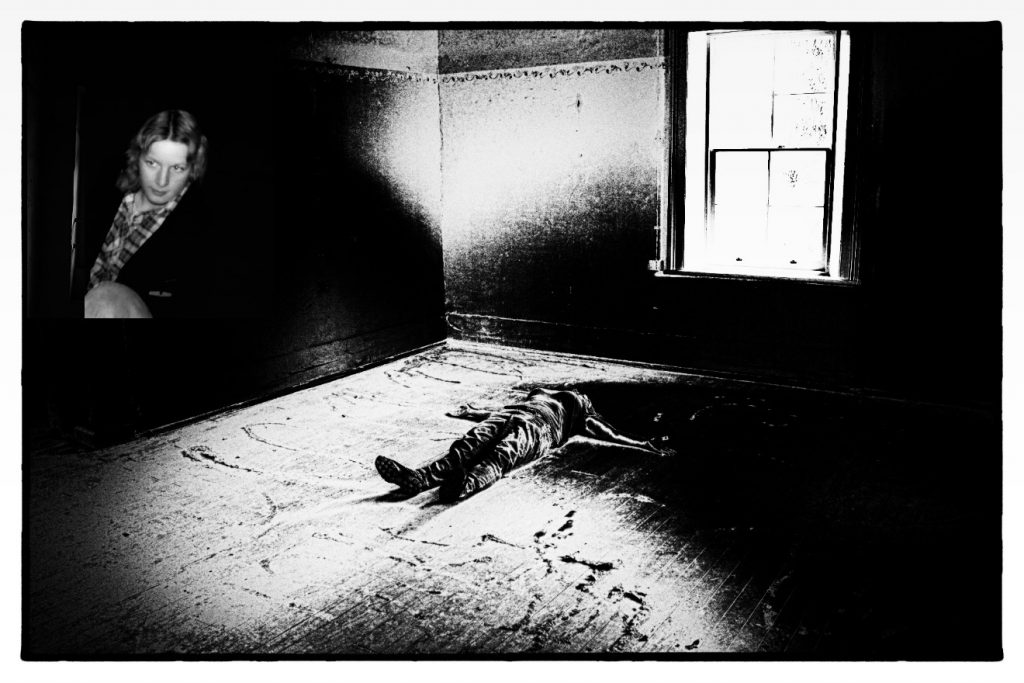

Sandie is lying on her back on the floor, arms spread out, in the middle of a cell at the Kamballa Special Unit at Parramatta, four decades after being imprisoned there. There is a photo of Sandie as a teenager collaged onto the wall.

Sandie Jessamine is a writer, transpersonal art therapist and writing mentor who lives in Sydney. She spent fourteen years teaching creative writing to inmates in New South Wales prisons. She has also worked as a health educator, an alcohol and other drugs counsellor, and a Dru Yoga teacher specialising in trauma yoga. She is a strong advocate for the rights of forgotten Australians and people living with mental health conditions.