By Katie Brebner Griffin

I’ve found that, for most of the time that I’ve been disabled, I haven’t behaved in a way that would be classified as a ‘leader’ in the disability space.

When I was first diagnosed with severe endometriosis, I thought it would be a relatively minor inconvenience that I’d have to address via a trip to day surgery every so often. Like many nineteen-year-olds, I was wrong, and in a lot of ways.

The pain and myriad of symptoms that I’d experienced for five years were to become lifelong companions. I would add more types of pain into the mix as I went along. But I thought this wouldn’t be that bad, as this is what everyone I’d been exposed to conveyed to me. Discussions of minor surgeries, quick recoveries and hormonal treatments that work really well for the majority of people. I had no reason to think that this wouldn’t be true for me.

It was a few years down the road when some of the cracks in the easy breezy world of chronic disease management appeared. I’d discovered by then that chronic pain, particularly reproductive organ-induced pain, was just something you’ll learn to deal with. So, just live with it I did.

At this time, I was in the process of applying for my first professional job as a graduate nurse. I was nervous about the prospect of starting in this important vocation for a whole variety of reasons, but I was most concerned about how I would tolerate the physicality of the job. In my placements, I would come home with numb, swollen feet and legs from standing for so long. I exacerbated an existing back injury, because that was what all the qualified nurses did. I had chronic UTIs whilst working in a job famous for its lack of toilet breaks. I didn’t know if I was quite literally up to the task of full-time nursing.

I was advised by mentors not to disclose my chronic health and pain conditions. This advice was given out of genuine care for my employability. In a competitive hiring process, when there were thousands of entirely able-bodied candidates available to choose from, this seemed like the right advice to take. I didn’t consider myself disabled at this stage anyway, rather someone that had a few conditions that were entirely private.

I wanted to be as appealing to the hospitals as possible. I never considered that disclosing a disability or chronic condition could be a way for employers to begin the process of providing reasonable adjustments or support. I considered my disability as my problem or shortcoming, something for me to deal with privately. I wasn’t a trailblazer, proud to declare what I dealt with behind the scenes. I abided by the ableist pressures to be silent, attempt to adapt – or more accurately, fall apart – out of view and pretend I was dealt the same hand as anyone else.

I wish I could say this is entirely not the case in the present. There are still strained voices and panicked questions of “You don’t need adjustments, do you?” in job interviews. It would be naïve to think that my answer wouldn’t affect the outcomes of these interviews, whether consciously or not. The structures in which we work and are employed are still built for an extremely outdated idea of who the worker is. It’s still inherently difficult for disabled people, who may require additional provisions and allowances, to enter and stay connected to the workforce.

In the present, we are hopefully in a place of transition. If we aren’t already, we need to be. I’m a disabled person who is at the highly privileged end of the spectrum of disabled people, and I don’t shy away from that. But if anything, my privilege paired with my struggles to find an appropriate, supportive workplace highlights that this issue must be in a dire state across our community.

I need a workplace that provides the equipment, considerations, and security we all need and deserve. Further to that, I want to be recognised for the unique skillset I can bring to an organisation; a combination of my analytical and communications skills, but also how the perspective I bring as a woman with disability is infused in and enhances these skills.

Although it doesn’t feel particularly revolutionary, I declare my disabled status these days and bring it into relevant conversations in my workplaces. It’s in the hope that if I can eventually claw my way up, I’ll have filled some of the gaping potholes and cracks along the road to equity, so that others can hopefully follow along more easily.

Whilst at first blush I don’t think I have the answers to the barriers facing the disabled community, I can see now, as a proud disabled woman, I actually do. The able-bodied community needs to go to the extra effort to make it possible for us to be meaningfully included. Have us in your boardrooms, houses of parliament, the managers’ officers at the local fast-food joint. But also have us in positions at all levels of organisations, make work a feasible option.

To bring about a world in which young women do not see their disabilities as only a private issue, I want to see disabled people making public policy decisions both at the governmental level, and at the local. Most of all, I desperately want that not to be a radical wish.

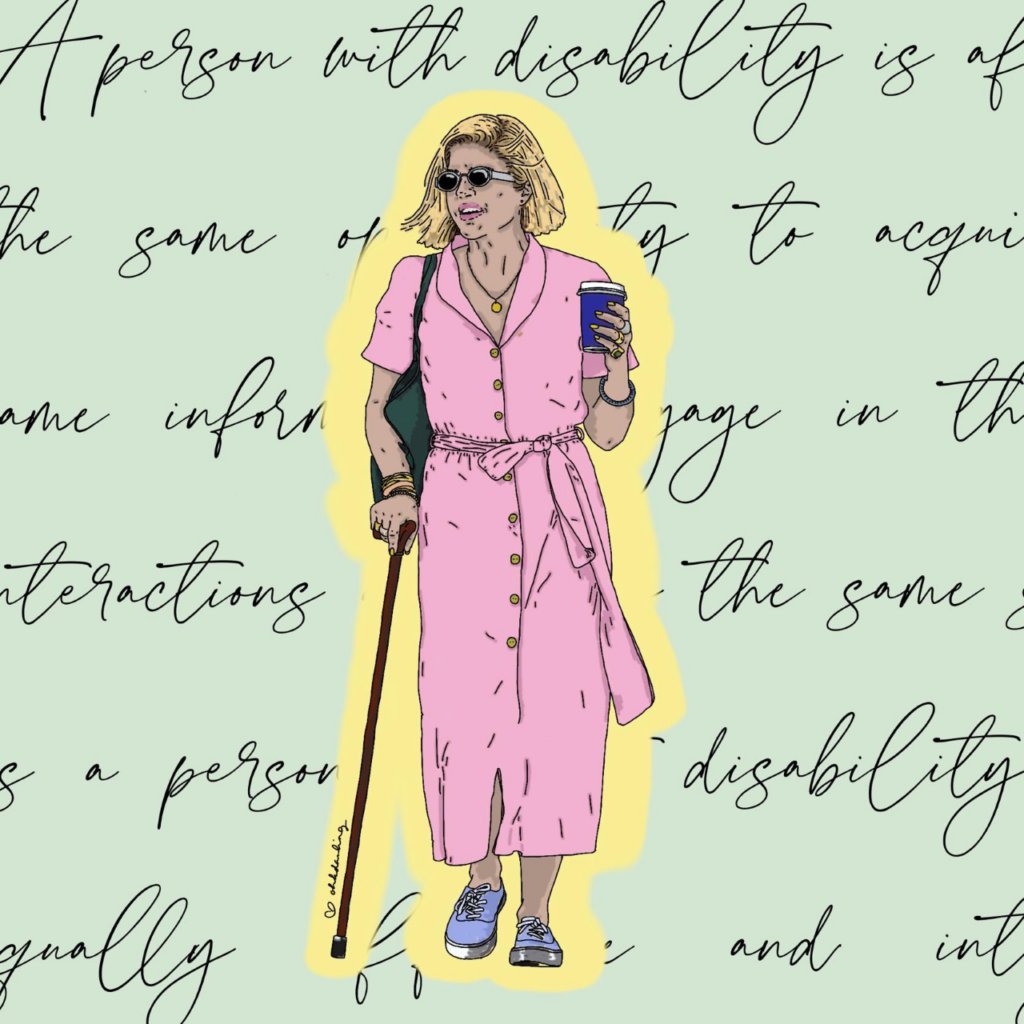

Katie Brebner Griffin is a social impact researcher and advocate based in Naarm. She explores her experiences through writing and illustration at @ohkdarling.