By Renay Barker-Mulholland

My early childhood is filled to the brim with bright, fun memories, and many examples of leadership from the strong women who led our family. My seemingly endless days outside, enjoying idyllic childhood activities like fishing for tadpoles in the creek, climbing trees, and jumping on trampolines. I spent countless hours in my Aunties’ homes, and just as many nights giggling with my cousins into the wee hours. There wasn’t just a single matriarch however, and all the women who led us were stalwart, with unwavering love and support all round. They all told me I was just as valued as everyone else, and as far back as I can remember, I was encouraged to ‘break the glass ceiling’.

Although my community was large, I lived in a one parent household. My mum became a single parent when I was young, and her own experiences had shaped her into a staunchly independent, fiery woman. I would often tag along while my mum volunteered at the local community centre, where I saw her leadership in action. She was an advocate for tenants in community housing, organised support groups for domestic violence survivors, and ran the committee. From this support and engagement with people from all walks of life, I recognised early that my life was different from the mainstream and the older I grew, the more apparent it became.

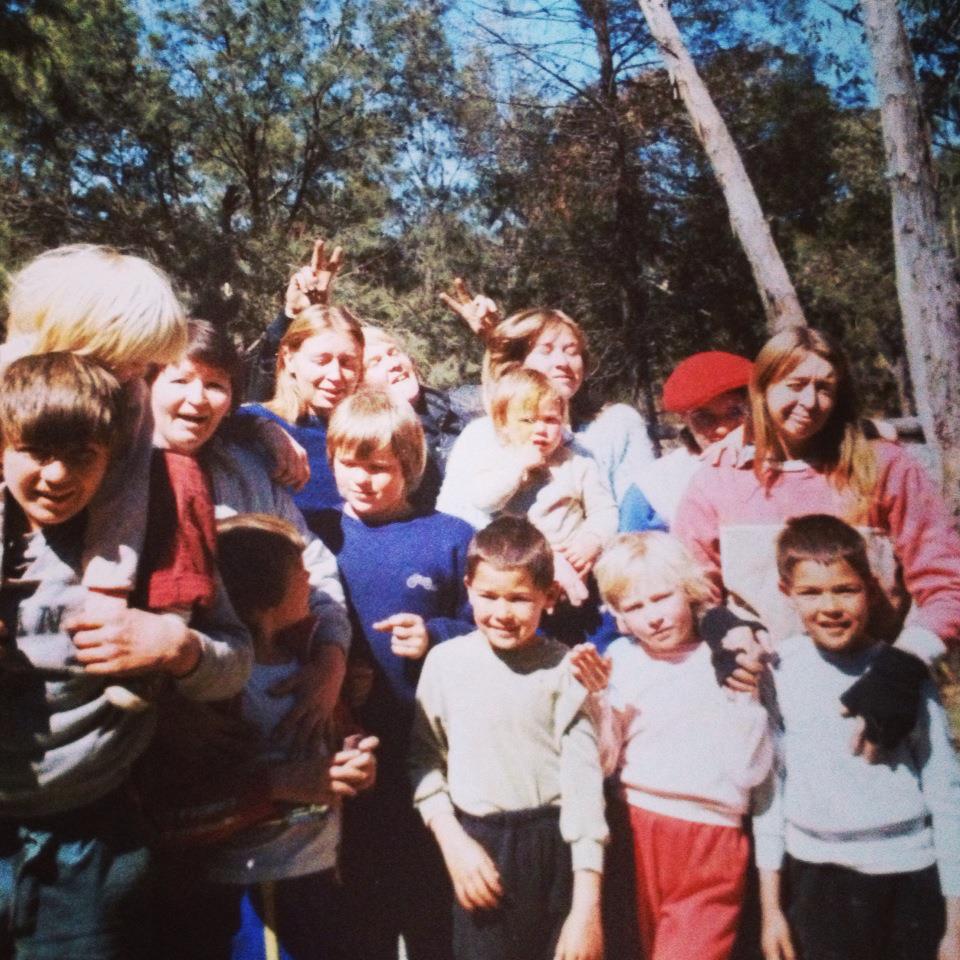

A large group of people stand close together for a family photo with a mix of adults and children. They all are wearing various 1980s style tracksuits. Behind them is thick bushland.

The most obvious difference was financial, we were dirt poor. If I wanted to play with a new toy, I would have to make it myself. If I wanted to read a new story, I wrote my own. My family discussed gender (in)equality, but our model for rejecting gender stereotypes came about when mum began paid work outside the home and I unwittingly became a latch key kid. Though the money coming made a difference, I benefited in other ways. Those times home alone contributed to my growing independence, I learned that I liked my own company. This appreciation and strength of myself was to be severely tested though, as without warning my mother announced we were to move interstate, and away from our family.

A young Indigenous girl with light brown skin and dark blonde hair, wearing a red jumper, is crouching down to play at the beach. She is looking at what she holds and behind her is a red plastic washing basket sitting on the sand.

The move was a game changer. I felt an isolation I’d never known before and being separated from my community was like having my lifeline cut. In the first 5 years after relocating, I attended 5 different schools and it was a baptism of fire in making new friends, and a hard lesson on how insular small towns can be. Before I knew it, high school was thrust upon me, and although I had made a couple of friends, it was not long before I found myself being ‘othered’. The world tells teenage girls (very convincingly) that they have to be a particular way to be accepted and I was definitely, consciously or otherwise, non-compliant. I have a sometimes-dangerous habit of pushing back when I am challenged, and the more I was socially excluded, the more I revelled in not fitting the mould. My independence served me well however, especially when I was forced to start over time and again at a brand-new school.

It was not long after I had started at my fourth high school, when I was invited to join some girls for lunch. Katie* was wearing a new scrunchie, and *Lisa had decided that it looked ‘stupid’, so berated Katie for her fashion faux pas. I was silent in the moment but approached Katie later, and encouraged her to wear whatever she liked. That conversation became a watershed moment for Katie, from that day on she had the confidence to respect her own opinion over others.

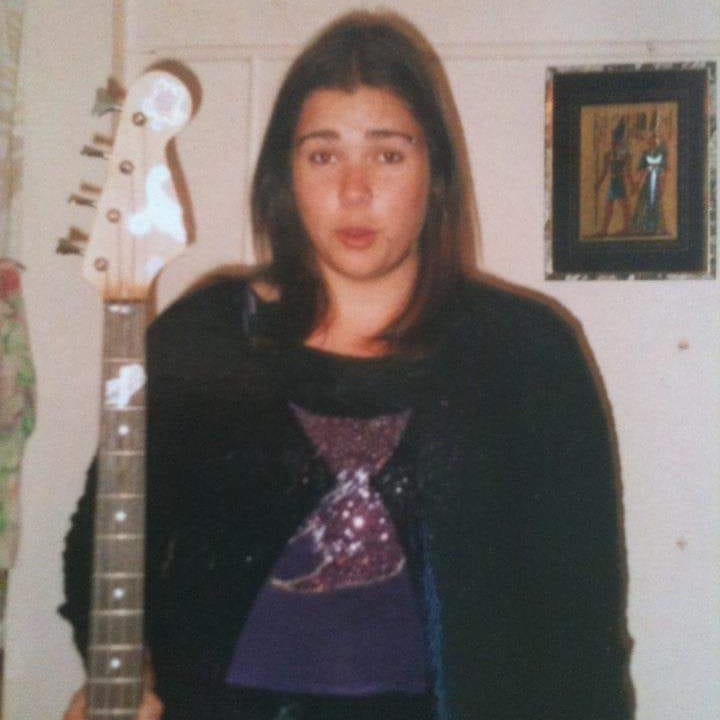

A teenaged Indigenous girl, with light brown skin and dark brown hair stands holding a bass guitar awkwardly. She is wearing a sparkly purple top under a fluffy black jumper.

Word of this conversation spread quickly around our little school, and perhaps spurred on by their own newfound confidence, a slow trickle of people began approaching me to share my company. These kids all had their unique quirks, and all were welcomed in our band of merry misfits. As we sat tucked together under a staircase at school, I rejected the notion of popularity altogether, and declared myself Queen of The Outcasts. The friendships formed during these times continued for many years, and it’s a title and crown I would still proudly wear.

I naively didn’t recognise the leadership I showed throughout these times, not until I had the benefit of hindsight. Oftentimes when I see an old photo of myself, I so desperately wish I could go and tell my 15-year-old self what I see now. Just like the women I learned from, I was self-assured, helpful, smart, and compassionate. A leader. A leader who knows that although my light may shine brightly, it never dims another. Someone who supports and encourages others to see the fire within themselves, and that’s something I will always endeavour to do and to see.

Me, embracing my difference, now.

A selfie of an Indigenous woman wearing a pink tshirt, and black rimmed glasses. She has rainbow coloured shoulder length hair.

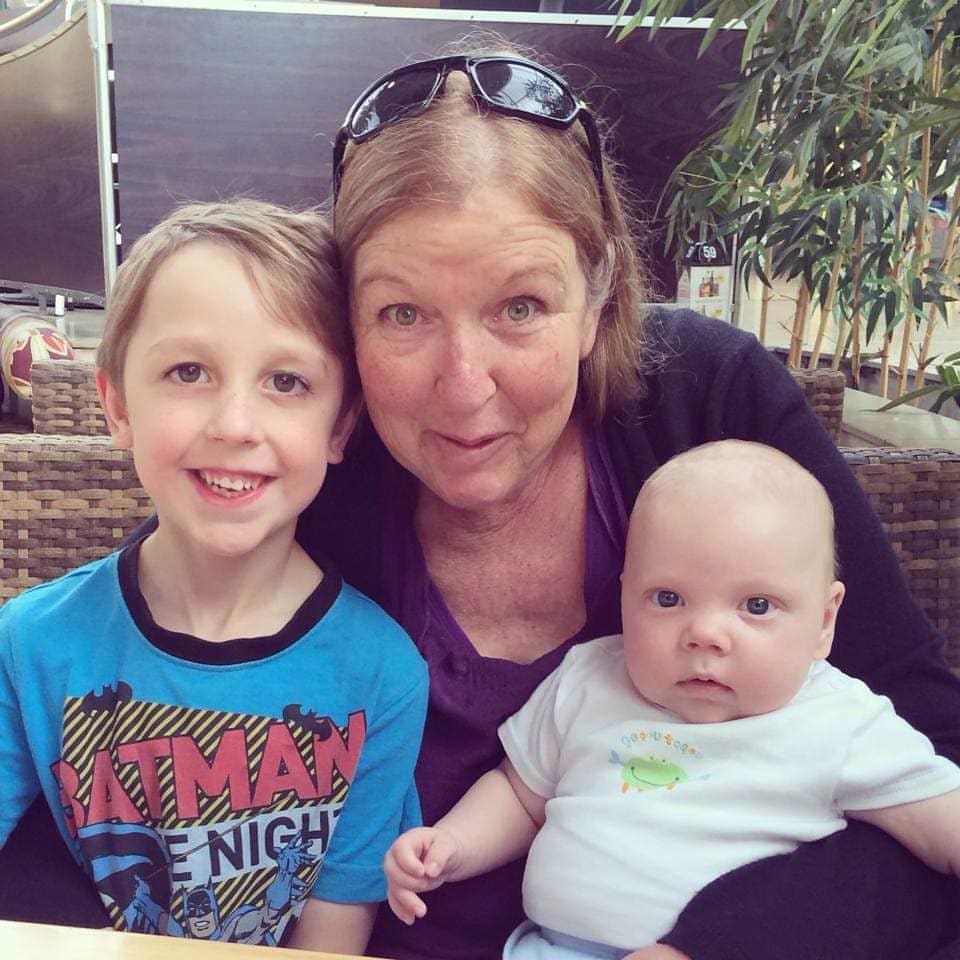

My beautiful mum, and her grandbabies

A middle-aged white woman sits between two young children, cuddling them and smiling. They are all facing the camera.

Renay Barker-Mulholland is a proud Biripi Daingatti woman who has been living with disability and chronic pain for many years but a wheelchair only for a few. She has Ankylosing Spondylitis, Fibromyalgia, Depression and Anxiety.