As a late diagnosed Neurodivergent woman, any updates in psychiatry are of prime interest to me. Not only as someone who is directly impacted, but also as the mother of a potentially Neurodivergent child. There is still much reform and activism needed to put an end to the stigma and stereotypes that bombard Neurodivergent individuals, which are born from the very guidebook that medically defines our unique brains, the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition).

On 18 March 2022, a revised version titled DSM-5-TR (Text Revision) – what a thrilling title – is due to be released. The DSM is important not only in accessing accurate diagnosis and treatment of all learning and psychosocial disabilities, but also in identification and support for co-occurring mental illnesses (such as eating disorders, anxiety, and depression). Currently, there is still a major gender gap in diagnosis for Neurodivergent Autistic women. Autism Spectrum News highlighted that a decade ago, it was believed that boys were four times more likely to be diagnosed than girls. Five years ago, a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies concluded that the true ratio may be closer to three times more likely in males. There is currently no definitive reason as to why more boys are diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) than girls. Below, I share my own extended diagnostic journey and my hopes for the future of psychiatry and neurodivergence.

For those who are new to Neuro-lingo, here is a brief summary. Neurodiversity, coined by Judy Singer in the 90s, defines the diversity and variation of cognitive functioning in all people. Everyone has a unique brain and therefore different skills, abilities and needs. Neurodivergence defines cognitive functioning which is not considered ‘typical’ (such as Autistic, Dyslexic, and ADHD people). Neurodivergent describes people with neurodivergence. The term Neurotypical describes those people with the most common cognitive functioning, noting it’s not neuro-normal, just most common. In a nutshell, Neurotypical is the most common brain type, Neurodivergent is a different brain type, and Neurodiversity is every brain. Clear as mud? Cool, now for some historical context.

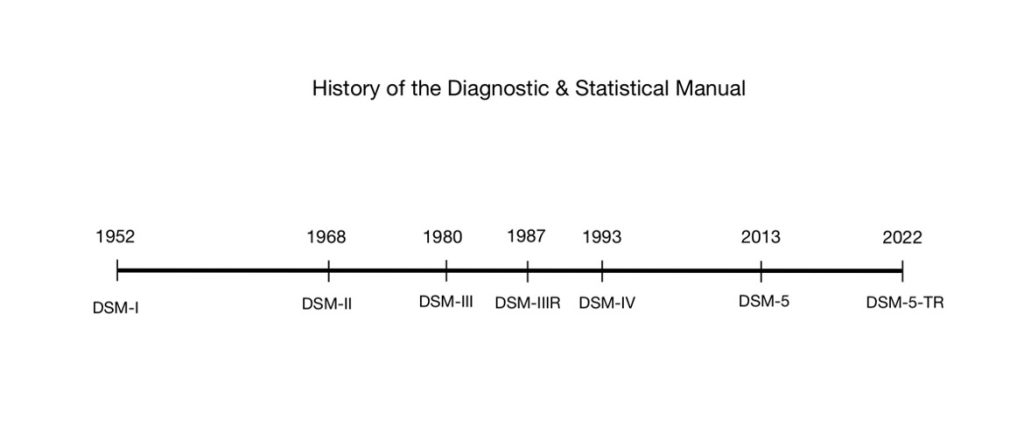

The DSM was originally created in the 50s by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) as a guidebook for mental health professionals. Like a dictionary, it enables a standardised form of communication on mental health to the broader community. The DSM-5-TR will be the great-great-great (you get the picture) grandchild of the original DSM-I, which was first published in 1952. It has been 9 years since the 2013 edition of the DSM-5 was published. This update will be the sixth major release in the 70 years of its existence. Periodic revisions are undertaken to ensure the manual reflects current science. Unfortunately, science moves a lot slower than people would like it to, but there is ongoing improvement, nevertheless. It’s far from a perfect tool, that I acknowledge has caused much damage within our disabled community, but it’s what we currently have.

In Australia, the DSM-5 is currently the primary system for identifying mental health conditions. However, the World Health Organization (WHO) just made the eleventh revision to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) which is also sometimes used. Notably, the ICD-11 update has included more information regarding gender differences in ASD. It is my hope that we see the DSM-5-TR also head in this direction of bridging the gender gap in diagnosis. ICD-11 states:

“Some individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder are capable of functioning adequately by making an exceptional effort to compensate for their symptoms during childhood, adolescence or adulthood. Such sustained effort, which may be more typical of affected females, can have a deleterious impact on mental health and well-being.

Males are four times more likely than females to be diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Females diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder are more frequently diagnosed with co-occurring Disorders of Intellectual Development, suggesting that less severe presentations may go undetected as compared to males. Females tend to demonstrate fewer restricted, repetitive interests and behaviours than males. During middle-childhood, gender differences in presentation differentially affect functioning. Boys may act out with reactive aggression or other behavioural symptoms when challenged or frustrated. Girls tend to withdraw socially, and react with emotional changes to their social adjustment difficulties.”

As people with disabilities, we face discrimination and barriers that restrict us from participating in society on an equal basis with others every day. We’re commonly denied our rights to access fundamental systems, including education, employment, and healthcare, and are often siloed into segregated settings. There are already so many barriers that our community face, but entry into this community through receiving a diagnosis remains one of the biggest. Disproportionately, it is women and gender diverse people who go years being either undiagnosed or suffering the trauma of misdiagnosis. The psychiatry field is just beginning to address the ways in which gender might influence diagnosis, assessment, treatment planning, and the assessment or success in intervention.

To help you understand the causal effect of diagnostic criteria in a real life, here’s my late diagnostic journey, which unfortunately isn’t an uncommon one for Autistic women and gender diverse people. I first stepped foot into a mental health professional’s office at the age of 23. This wasn’t because it was my first struggle with emotional or cognitive health, on the contrary, I had battled the black dog and his mates most of my life, but I had finally hit breaking point. Another issue with diagnostic and mental health accessibility is only receiving help when our struggles are so severe that we cannot function at all, and generally not a second before – but that is for another day.

My General Practitioner (GP) sent me to a psychologist after being put on stress leave due to ‘anxiety’ and ‘depression’ caused by a stressful work environment. I remember the first question the psychologist asked me, “how was your childhood?” to which I responded, “um, good.” What kind of a question was that? I was well fed, given a good education, and I even had parents who loved me. Trifecta. We went on to discuss my toxic boss and huge workload and kind of avoided getting into the nitty gritty of how I viewed the world and interacted with it. A few months in, my therapist handed me a copy of The Highly Sensitive Person by Elaine Aron. What I would come to learn of as the socially acceptable label of Neurodivergent. A year later, I got a progress report stating biggest concerns: perfectionism and avoidance. To which I laugh at now, in retrospect, as that was just the tip of the iceberg.

It took three years of therapy just to open up enough to share my sexual assault. In hindsight, I don’t think I had the greatest trust in that psychologist. I don’t blame her for that, I believe it is a product of a lifetime of not showing my true self to the world – of course that would extend to therapy, consciously or not. I didn’t trust anyone, not even myself. When you spend your life being told you’re wrong. The way you think it wrong. The way you look is wrong. The way you feel is wrong. You start to gaslight yourself.

While on stress leave for those few weeks I was in a car accident. It wasn’t major, it wasn’t even life threatening. My car was towed but ultimately salvaged. The couple that hit my car physically intimidated and verbally attacked me in the aftermath when I tried to call police to the scene. I walked away a little shaken up but seemingly unscathed. I didn’t know at the time that it would lead to many surgeries, chronic pain, years of legal proceedings and ultimately the discovery that I am Neurodivergent.

After three years, multiple surgeries, many specialists, and too many physios, my third pain doctor told me that he had done everything he could and that it was time to start thinking about seeing a psychiatrist. I had no idea what to expect. I knew enough about chronic pain education to understand that “it’s all in your head” meant that how we experience pain is literally in your brain. So, it was time to see a different kind of brain doctor. The psychiatrist I saw diagnosed me with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and recommended EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) therapy to treat it. And off I went to a new psychologist to try a new therapy. It helped my specific PTSD symptoms related to driving but beyond that, I was still feeling lost and hopeless.

When I started to research PTSD, I came across more and more information on the overlap in symptoms with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and started to think that maybe that was what I had all this time. After growing up hearing about the stereotypical ‘little boy jumping off the walls’ presentation, I never thought ADHD could relate to me. But reading how it can be a very internal experience of dysregulation and how that can look in women gave me my first ‘ah-ha’ moment. I mentioned this to my GP, and she agreed that it sounded like it could explain some of my troubles, so she wrote me a referral to a psychiatrist who specialised in ADHD. Fast forward six months, and I walked into my assessment with this specialist psychiatrist, more confident than ever that I truly did have ADHD.

In preparing for my appointment, I gathered reports from school and examples from family of my behaviour across the lifespan. I read up on ADHD, with Attitude Magazine being a favourite source, discussing everything from executive dysfunction to sensory processing issues. I joined ADHD Facebook groups and was convinced I’d found my tribe. Not once, and I’m embarrassed to admit this, did I think I was Autistic. Not because I had read about it and it didn’t fit, but because it was rarely ever brought up in ADHD articles and forums. Autistic traits were commonly explained in reference to ADHD, not autism. On the rare occasion that autism was brought up in ADHD forums, it was usually with a flavour of disgust or dismissal. Sensory issues and communication struggles were all openly talked about as being ADHD related, so I never thought I needed to look further.

The day of my assessment came, and I was impressed with how thorough the psychiatrist was compared to the one who diagnosed my PTSD. At the end, I held my breath as he asked me what I thought I had. I told him that I already knew about the PTSD, but I was confident that I had been ADHD my whole life. Then he asked if there was anything else, which had me perplexed. “Um, anxiety and depression,” I said. To which he responded, “you also have an Autism Spectrum Condition.” Which left me feeling very confused, what was autism? Wasn’t it people who didn’t have friends and couldn’t make eye contact? That isn’t me. He gave me a cartoon example of how an Autistic person interacts with others – and it wasn’t overly stereotyped, but I still wasn’t convinced. He gave me a bunch of resources and told me to read them and see what I thought.

As you can imagine, I went home and spent the next few months obsessed with reading everything I could possibly find on ASD. And even more so than when I discovered ADHD, I felt understood and seen for the first time in my life. This was met with the bitter taste of how could I not know? I’ll tell you how. Because the institutions that have defined these conditions and neurotypes are rooted in gender bias, with histories of male doctors studying male patients. I went on to receive a diagnosis for an eating disorder I’d lived with since I was 11 years old, that hadn’t been picked up previously due to the atypical presentation from my atypical brain. My story isn’t an uncommon one. Many women and girls go through life with invisible disabilities having to fight the same uphill battle without any access to support or validation.

As highlighted above, rates of autism prevalence suggest that boys are, on average, 4 times more likely to have autism than girls. However, it is finally coming to light that this number hides the true incidence of autism in girls and women; studies are now showing the true ratio to be closer to 1:1 (that is, one boy for every girl). An Australian study published last month highlighted that the lack of initial recognition in girls with ASD is the biggest problem creating ascertainment bias in ASD research. It stated that “[u]nless the gender samples are truly representative, the proportions of the characteristics cannot be compared.” The study found that 80% of girls with ASD are undiagnosed at 18 years old. This disproportionate diagnosis pattern for girls has massive flow on effects for mental health treatment and quality of life in these individuals.

According to the ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics), in 2015, an estimated 164,000 Australians had autism. Now, if we factor in an error margin for missed diagnosis in girls and women, this number will look more like 250,000 Australians – and that’s being generous, as the true number is most likely much higher. This is 1% of the population. Now can you imagine 86,000 Australian girls and women currently unaware or undiagnosed as Autistic?

The Australia study mentioned above noted that “ASD is not a mental illness, and an individual may have one or more [mental illness comorbidities], but without upstream causal factor of ASD identified, she will never fully get to grips with her condition and gain psychic relief by understanding herself.” In non-scientific language, this basically means that without acknowledgment of their underlying ASD, standard mental health treatment is ineffective. I would further add that mental health treatment for an Autistic girl or woman is not only ineffective, but in many cases harmful. I am personally an example of this. My mental ill health was treated for years to no relief until I was diagnosed accurately and given access to specialised psychological supports.

Common co-occurring conditions for Autistic people include, anxiety, depression, eating disorders, sleep disorders, and more. Treatment of these conditions needs to be tailors to Autistic needs and Autistic brains. Currently most treatments for these conditions are based on studies and results of Neurotypical individuals. Most psychologists and mental health providers still have a very limited understanding of autism in girls and women. It is not surprising to me that a 2019 study found that 1 in 5 women with ASD and ADHD attempts suicide, compared to 1 in 11 men with these conditions. Women not only have a harder time accessing appropriate diagnoses and treatments, but they are also usually hyperaware of their differences given how society raised them to be more socially aware – one of the very factors that causes issues identifying social reciprocity difficulties in the diagnostic process.

Parents of Autistic daughters will often share frustrating tales of how difficult it was to get a proper diagnosis, while many Autistic women, like me, did not receive diagnoses until well into adulthood. We camouflage our Autistic traits because we want to survive. We learn from as young as 6 years old about social hierarchy and the consequences of standing out. Unconsciously, we study behaviour in movies, in family, in friends and we learn quickly how to conform and hide in plain sight. Sometimes, completely unaware that we are even doing it and that it isn’t a normal human experience – doesn’t everyone have to hide their true nature?

By the time we reach adulthood and step into a mental health professional’s office, we are convinced as much as they are that we couldn’t be Autistic just because every stereotype is a ‘male savant’ or ‘anti-social nerd obsessed with trains or penguins’: like Rain Man, The Accountant, Sheldon Cooper from The Big Bang Theory, or Sam from Atypical. Most of the time the question, “could she be Autistic?” isn’t even raised. And yet, most of us have many interactions with mental health professionals before ever even receiving a diagnosis, presenting with eating disorders, trauma, sexual assaults, suicidal thoughts, anxiety, depression, and the list goes on. Why are these things not automatically flagged for ASD and ADHD screening in women? We already know how much more common they are in the Neurodivergent population. This knowledge should be informing any diagnostic criteria updates in an attempt to bridge the gender gap.

With the diagnostic criteria still based largely in how ASD and other neurodevelopmental disorders present in men, revisions to the DSM are important to correct this gender inequality. Unfortunately, the updates are slow and usually rather conservative in any changes. Just because the entire Neurodivergent community recognises that ASD in women, girls and gender diverse people is much harder to identify, doesn’t mean the DSM is ready to highlight that – although it’s nice to see the ICD-11 starting to do so. Studies on gender differences in Neurodivergent presentations are still in their infancy and the American Psychiatric Association (APA) like to have their science overcooked before adding a new or updated recipe. This is slowly changing as more and more funding and research is starting to pop up. So patiently we wait and hope that that time is closer than we think.

As Dr Michael First of Columbia University highlights in a 2013 PBS interview, “One of the rules of the DSM, which has been there since the very beginning, is that it’s not to be used as a cookbook. Clinic judgement should be used in the decision-making process to make a clinic diagnosis.”

The problem with this statement is that clinical judgement is inconsistent and sadly commonly ill informed. So many women are still being told by mental health professionals that they couldn’t be Autistic because they can make eye contact. The lack of awareness broadly in the mental health profession about how Neurodivergent women and gender diverse people can present, alongside common comorbidities, is astounding. If we are not going to highlight this in the diagnostic criteria, then we should at least be educating our psychiatrists, psychologists, and general practitioners in this disparity.

So, what should we expect in this latest update of the DSM? According to Psychiatric News, the revised DSM-5-TR will include updates and clarifying modifications to the criteria for more than 70 disorders, as well as updates to the descriptive text. It will also examine the impact of racism and discrimination on the diagnosis and manifestations of psychosocial disabilities and mental disorders. The update includes revised diagnostic criteria for several disorders, including the following diagnoses:

- Attenuated Psychosis Syndrome

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Avoidant-restrictive Food Intake Disorder

- Bipolar Type I and Bipolar II Disorder

- Cyclothymic Disorder

- Delirium

- Major Depressive Disorder

- Manic Episodes

- Persistent Depressive Disorder

- Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Children

- Substance/medication-induced Mental Disorders.

Apparently, there will even be some long overdue updates in terminology, including:

- “Desired gender” is now “experienced gender,”

- “Cross-sex medical procedure” is now “gender-affirming medical procedure,” and

- “Natal male”/”Native female” is now “individual assigned male/female at birth.”

Approximately 75% of the disorder texts will have significant revisions, with the most extensive changes being within prevalence, risk and prognosis factors, culture-related diagnostic features, sex and gender diagnostic features, association with suicidal thoughts or behaviour, and comorbidity.

That all sounds like it is in the right direction. However, I will continue to hold my breath for the actual outcomes. I’m happy to see sex and gender mentioned in the update, with language that is validating of the Trans community beginning to be used by the mental health profession, but I will be very interested to see how they go about identifying the impacts on diagnostic features. I hope that there is more of a push to move towards identifying internal experiences and less on simply outward behaviour – especially given this is the main problem in diagnostic identification in women who camouflage. As we all know, the brain is a very complex organ, and depending on many influences in your life (including cultural, cognitive, gender and beyond), it can reveal its inner workings very differently. I do believe that the DSM will catch up one day, it’s just a matter of when.

I’m thankful for the mental health professionals that are already ahead of the curve in identifying and treating, even though they are sadly few and far between. I just hope that more services and support become available and accessible to help those of us who don’t fit the cis-white-male mould. We deserve equal rights to mental health and disability support. It starts at the top. And until the medical profession steps up to ensure equality within the diagnostic manual, we will still need to share our stories and advocate loudly.

For Neurodivergent women and gender diverse people to thrive, it’s important we have access to a timely and accurate diagnosis, and the informed supports that come with it. A delayed or missed diagnosis can impede our education, development, social and community participation, and most importantly, mental health. With delayed and missed diagnosis, we are far more vulnerable to internalising problems and developing comorbid mental illnesses. As our understanding of neurodivergence in women and gender diverse people continues to grow, it is important to stay updated on the best ways to identify and support this incredible community of Neurodivergent individuals. It is my greatest hope that the updated DSM-5-TR makes new leaps towards increased diagnostic accessibility to all Neurodivergent humans, especially us women and gender diverse people. Without accurate and inclusive diagnostic criteria, disabled and Neurodivergent people are left without access to basic human rights. We will not stop advocating until we have equal access to health care and our fundamental rights are met by government and society.

Annie is a 30-year-old disabled neurodivergent lawyer, mother, and the founder of Neurodivergent Millennial, a blog dedicated to neurodivergent adults – focusing on mental health, employment, self-advocacy, and parenthood.

See our full leadership blog here: Leadership Blog

Would you like to contribute?

If you want to submit a blog post on leadership, you can learn more here or email our Blog Editor at blogs@wwda.org.au.

Want to learn more about LEAD?

If you would like to learn more about WWDA’s new project, LEAD, find out more on the LEAD page.

Disclaimer

The blog posts do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of Women with Disabilities Australia (WWDA), and blog posts are contributions made by women, girls or non-binary persons with disability about what leadership means to them. All possible care has been taken in the preparation of the information contained in this document. WWDA disclaims any liability for the accuracy and sufficiency of the information and under no circumstances shall be liable in negligence or otherwise in or arising out of the preparation or supply of any of the information aforesaid.